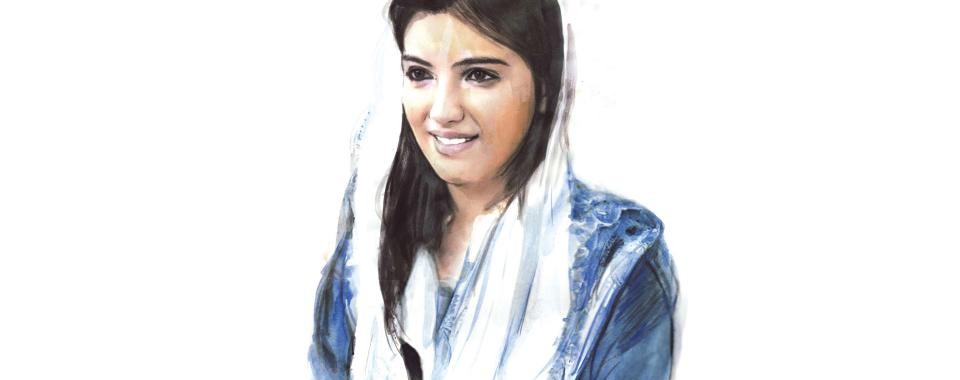

Find Aseefa Bhutto Zardari’s interview with the Rotary Club below. She is the official Rotary Polio Ambassador.

Before her family was forced into exile, before her mother was assassinated, before her father became president, Aseefa Bhutto Zardari was known for something simpler, but in some ways equally powerful: In 1994, she became the first child in Pakistan to receive the oral polio vaccine, as part of the country’s first National Immunization Day. Benazir Bhutto, then prime minister, gave the drops to her daughter herself, a compelling endorsement of the nascent campaign.

“I was a baby at the time, so I don’t remember it,” says Bhutto Zardari, now 22. “But the moment was an inspirational one for the nation, and encouraged women to believe that polio drops were and are safe.”

In 1988, at age 35, Benazir Bhutto became the first woman elected to lead a Muslim country. She was assassinated in 2007, just months after she had returned to Pakistan after almost nine years in exile. But Aseefa Bhutto Zardari – whose father, Asif Ali Zardari, served as president of Pakistan from 2008 to 2013 – is carrying on her mother’s work. As a Rotary polio ambassador, she meets with officials, visits schools, and talks with families of health workers who were killed while working to vaccinate children.

Bhutto Zardari has raised the profile of the polio eradication campaign in Pakistan and around the world. She writes about the topic for the Huffington Post and joined Rotary International General Secretary John Hewko onstage at the 2012 Global Citizen Festival in New York City’s Central Park. On Twitter, with more than half a million followers, she encourages people in Pakistan to support ending polio and chastises those who stand in the way. In April, she invited two other prominent women in Pakistani politics to join her in the polio eradication effort, a move that garnered media coverage across the country.

In 1994, the year Bhutto Zardari received those first drops of vaccine, Pakistan had an estimated 35,000 cases of polio. As of 10 June, 24 cases had been reported in the country in 2015. Bhutto Zardari, who is completing a master’s degree in global health and development in London, talked to us about ending polio in Pakistan, her future in politics, and prospects for peace in her country.

THE ROTARIAN: Recently in Pakistan, some parents who refused the polio vaccine for their children have been arrested. Are those arrests justified?

BHUTTO ZARDARI: There is a great ethical debate about whether the arrests are justified. Is it the right of the citizen to refuse care? Is it the right of the child to have the best health care? Personally, I don’t believe arresting people is the best solution. Parents want the best for their children, and they are trying to ensure their safety. Educating the parents and persuading them to let their children have the polio drops is more powerful and, although time consuming, will be more successful in the long term.

TR: You’re active on Twitter. If you could use more than 140 characters on Twitter to send a message to parents who choose not to vaccinate, what would you say?

BHUTTO ZARDARI: In the media environment today, so much of our lives and what we seek to do is oversimplified, often stripped of meaning and context. Much of what I say on Twitter about this topic [of vaccination] is directed at people in positions of influence who are abusing their position by taking an anti-vaccination approach, rather than at individual parents. I know that the majority of parents, even those refusing vaccinations, have their children’s best interests at heart.

To parents who have held off on vaccinating: Do not take rumors as truth or let people use health as a political or religious weapon. Your children’s lives are at risk, and by giving them two small drops, you can ensure they will avoid the suffering that polio can cause. Speak to families who have experienced polio personally. Talk to the polio workers and learn from them.

If we had to reduce it to a campaign slogan, I would say to those parents: Don’t rob your children of a future they deserve. Give them a chance. Let them get the polio vaccine.

TR: What is the future of the polio eradication campaign in Pakistan? How will you continue your involvement?

BHUTTO ZARDARI: There is a serious disconnect between the significant and targeted efforts put in by the provincial governments and the hands-off approach taken by the federal government. To ensure the best chance of success, we need collaboration with the federal and provincial governments in order to have a united front. Along with this, we need to focus on training more lady health workers [a program launched by Benazir Bhutto that has trained more than 100,000 women to provide community health services] and polio workers. These health care workers will be able to use their expertise to support other areas of our health service in the future, and we need to plan for this. I am committed to a polio-free Pakistan, but I’m also committed to a healthier Pakistan overall. For now my focus is on polio, but I hope to carry on my training to get involved in other areas of health care.

This campaign needs more resources, especially in the environment of fragile security that so many of our heroic vaccinators face. The PPP [Pakistan People’s Party, founded by Bhutto Zardari’s grandfather, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto] recently proposed that donors fund a security health corps to protect vaccinators as they attempt to reach children in dangerous areas. This is crucial to protect the lives of our vaccinators and to ensure the success of the program. I often hear of vaccinators returning from high-security-risk areas, such as Quetta, who were unable to reach children because of the danger. The conventional methods of taking the program forward may not be enough if we do not simultaneously address the security concerns.

TR: Will you go into politics?

BHUTTO ZARDARI: I have always been in politics. Since I was a child, I have been surrounded by it. With a mother who was prime minister twice and a father who served as president, it is impossible to avoid politics. I am keen to make my own mark and ensure that I have the skills to best serve Pakistan in the future. That is why I have dedicated so much effort to my education, specifically focusing on health care and humanitarian concerns.

TR: What was it like to grow up in exile?

BHUTTO ZARDARI: I spent a good portion of my life in Dubai. It was difficult to see the struggles my mother faced being away from our home. At the same time, it was inspiring to see how she was able to maintain a presence in Pakistan while in exile. My father was in jail, and she was petitioning leaders worldwide to help bring democracy back to Pakistan. Despite all of that, she always made the effort to help my siblings and me with our homework, and attend our school functions and plays. We were always hoping to return home, but she made sure we never felt lost.

TR: Your grandfather was executed under a military dictatorship, your father was jailed, your mother was killed. What drives you to risk your own security by staying involved? Why not walk away?

BHUTTO ZARDARI: Walking away is not an option. My mother, father, grandparents, aunts, uncles, brother, and sister have all committed themselves to serving Pakistan. They have all believed that they could have a positive impact. While to many, they are simply political figures, they are my family. I trust them, and they have shaped who I am. I will carry on the cause that they have believed in, and that many of them have died for, to honor them and to serve my country.

TR: What prevents you from focusing on the tragedy you have experienced?

BHUTTO ZARDARI: While there has been great tragedy in my life, I am also aware that I have been given great opportunities. I have been able to study, I have been able to travel, and I have been able to create friendships with people from all over the world. I have also been blessed with an incredible brother and sister and a wonderful father. The support I get from my family is a great comfort.

TR: One of your mother’s legacies was inspiring women and girls, including Malala Yousafzai, who calls your mother her role model. What will it take to develop more female leaders in Pakistan?

BHUTTO ZARDARI: Just as I have been blessed to have such an inspiring mother, I feel blessed to have had the opportunity to get to know Malala. She is exactly right in identifying how we will empower women to take the lead in Pakistan in the future: education. We must ensure that women and girls have access to quality education so they are able to obtain leadership positions. At the same time, we must make sure that men and boys are being educated about equality.

TR: Will your country and the region ever see peace?

BHUTTO ZARDARI: I have great faith that one day Pakistan will have peace. I pray for the day when people can look beyond the bombs and the bullets and see my beautiful country, where the people have so much talent and bravery. It is a region in deep transition. One can only hope that the challenges of rapid population growth in South Asia will motivate leaders to strive harder for peace, and that we will be able to work with our neighboring countries to form a more stable and safe environment for our families.

Host an event for World Polio Day on or around 24 October and spread the word in your community about Rotary’s role in the campaign to eradicate polio. During your program, watch an update on the state of polio at endpolio.org.

By Diana Schoberg

The Rotarian

20-Aug-2015